Reviewed by Peter G. Maxwell-Stuart

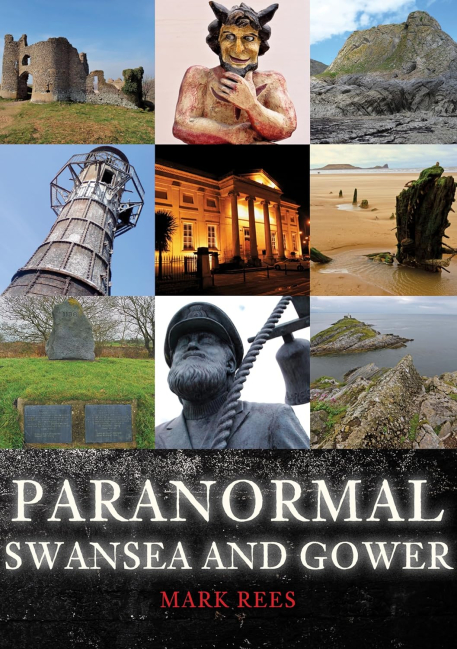

This book could be described as a ‘jolly romp’ through a large number of anecdotes largely talking about ghosts and people’s reported experiences of them. The material is drawn principally from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, although it deviates from time to time into the twentieth, and indeed, the final chapter is devoted to ghosts from that century. The collection is generously illustrated with photographs.

The author, Mark Rees, has published more than one book of a similar nature and has taken an active interest in investigating, with others, a number of alleged paranormal events. His account of these and historical paranormal events in Swansea and Gower is short and clearly designed for popular and transient reading, not an illicit or useless end in itself, but one which, unfortunately, turns out to be disappointing. The trouble is that a miscellany of extracts from historical and contemporary sources which does little but tumble one anecdote after another fails Aristotle’s test of a good plot – that it should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Even if one argues that miscellanies are not obliged to follow that recommendation, their individual components should. In other words, the story should get one somewhere. To the question, what is this particular miscellany for, the answer here seems to be ‘simply diversion’. But this fails a further test. Each anecdote says, ‘Such and such happened,’ to which reasonable questions are ‘Why?’ and ‘How do we know?’ Neither of these questions seems to have been expected by the author. He simply says, ‘A happened and then B and then C’ and so forth through the entire alphabet. Chapter 1 illustrates this disparate ramble. It gives us anecdotes about a ghostly horse, a poltergeist white lady, a witch and wise-women, (not necessarily the same thing), the Devil, fairies, a death-omen, fairies again, ‘figures’, a swan-maiden, and a stone.

The question of why the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were so fascinated by supernatural and paranormal phenomena is not raised, let alone answered however briefly, even though that question surely occurs, even if unspoken, to the reader, casual or not. To be fair, Rees does glance in the direction of the emergence of spiritualism, for example, and the improved technology of printing which helped to make newspapers more available, (pp.41-42), but there is no follow-through which would immediately have made the attendant anecdotes more interesting. Chapter 4, too, which recounts a number of anecdotes about haunted theatres, briefly mentions a possible connection between the emotions accumulated by constant performances in a theatre and the reports of ghostly sightings there, but does not pursue it in the direction of accumulated emotions elsewhere - in haunted landscapes, for example. An opportunity missed. I regret, therefore, to venture the opinion that this book is more of a potboiler than anything else, along the lines of Dickens’s Fat Boy, ‘I wants to make your flesh creep.’ Candyfloss is momentarily enjoyable, but cannot satisfy a hunger for something rather more substantial.

Dr Peter G. Maxwell-Stuart is Senior Tutor at the University of St Andrews