Reviewed by Tim Prasil

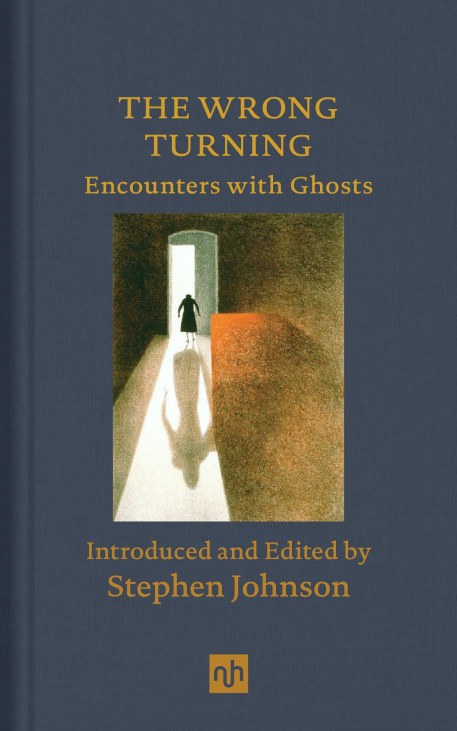

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of anthologies that focus on fictional ghost stories. There are so many, in fact, that some zero in on a particular type of ghost story, say, those written during the Victorian era or those set in winter. The Wrong Turning: Encounters with Ghosts is a new fiction anthology introduced and edited by Stephen Johnson, and published by Notting Hill Editions. While readers already invested in the rich history of ghost stories might find too many familiar, often-reprinted works in this volume, those seeking an introductory overview of the genre are likely to find The Wrong Turning worthwhile and enlightening.

When I say familiar works, I’m referring specifically to the book’s excerpts from Emily Brontë’s "Wuthering Heights" (1847), Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw” (1898), and M.R. James’ “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come for You, My Lad” (1904). In addition, there are the complete versions of Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” (1890), Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), and W.W. Jacobs’ “The Monkey’s Paw” (1902). These popular pieces take up about half of the book.

The newer and probably less widely known works include a 1944 selection from Flann O’Brien’s “Cruiskeen Lawn” column, which ran in the Irish Times; Lang Ying’s “Men Take Refuge from Ghosts in a Bath House,” first published, Johnson says, “in the years leading up to Chairman Mao’s devastating Cultural Revolution,” so the early 1960s; and Penelope Lively’s “Black Dog,” dated 1986. These pieces work well to suggest the broad and persistent appeal of ghost stories.

Some might wonder whether or not all of these works I’ve named are, indeed, ghost stories. While the tales by Bierce, Gilman, and Jacobs are certainly weird and at least flirt with the supernatural, do they really include ghostly ghosts? If we use a flexible definition, then yes, they do—and if we include psychological ghosts, then they certainly do. That’s how Johnson introduces the tales, referring to the “mental state” that evokes “terror, painfully heightened awareness (hypervigilance, as the specialists put it) and dreadful imaginings—half-waking nightmares beyond the conscious control of the sufferer.” In fact, this seems to be the focus of his choices.

Johnson also explains the book’s title when he says that “the notion of some kind of ‘wrong turning’” underlies many ghost stories that have achieved literary acclaim and stood the test of time. “No matter whether it involves a literal wrong turning or something more mysterious and elusive,” he writes, “in each case a character makes a mistake and places trust in the wrong kind of mental compass.” Johnson’s adds brief commentary before and after every work, and in the first few, he clarifies how the “wrong turning” idea applies. However, he lets readers apply the concept on their own around the time they reach “The Yellow Paper,” and in some cases, it can become tricky to locate any wrong turning. For instance, did the misstep of Gilman’s narrator occur prior to the narration, when she married a domineering and dismissive husband? Was it in this character’s failure to, at any point, wholeheartedly reject the so-called “rest cure”? (By the way, Gilman herself did rebel against that cure, and her doing so led to a different outcome.) Rather than conclude Johnson forgot his own organizing principle, I like to think his devious scheme was to nudge readers to think about what they’ve read in interesting ways.

This attempt to illustrate that there’s more to the ghost story tradition than some readers might assume compliments Johnson’s selection of old and new, canonical and marginal, works. Together, these make the book especially suited to uninitiated readers eager to enter and explore a haunted house with many, many rooms.