Reviewed by Tom Ruffles.

Mark Lamont has comprehensively analysed the famous 1901 Versailles case which formed the basis of Charlotte Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain’s classic An Adventure (1911). A large number of commentators have combed their book, and related documents, and proposed a variety of explanations to account for what happened to them. As a result it is now difficult to disentangle the various elements of the ladies’ experience because they have often been, in Lamont’s words, ‘fragmented … or simply misinterpreted’. In an effort to remedy these deficiencies he has scrutinised all the available evidence bearing on this enigmatic episode and laid it out clearly, allowing the reader to inspect it with a fresh eye.

According to Misses Moberly and Jourdain, on Saturday 10 August 1901, while holidaying together in Paris, they visited the chateau of Versailles. It was a warm overcast day and while wandering the estate in search of the Petit Trianon palace they became lost. The atmosphere was oppressive, and as they walked they met, and occasionally interacted with, a series of people dressed in old-fashioned styles and speaking French with unusual accents. One of these, a lady sketching in the gardens in front of the Petit Trianon, Moberly later decided was Marie Antoinette herself; Jourdain could not recall having seen her though they had walked right past her. Once inside the building the strange spell was broken. Back in Paris Moberly and Jourdain agreed the place was haunted, but only three months later did they discuss the events of the afternoon more fully and, believing something strange had happened to them that day, wrote independent accounts of what they claimed to have seen.

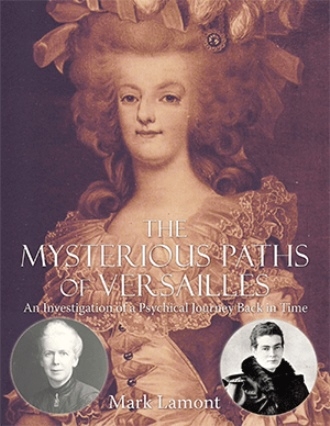

After extensive research, plus return visits, they concluded they had found themselves transported to the time of Marie Antoinette in 1789 and had seen the place as she remembered it, somehow entering into her act of memory as she recalled the place as it was just before the Revolution and the overthrow of the monarchy. A decade after the experience they published An Adventure under the pseudonyms Miss Elizabeth Morison and Miss Frances Lamont. It was well received by the public and eventually went into five editions, the last issued in 1955.

Lamont begins his book with biographical sketches of Moberly and Jourdain, followed by a brief history of the Petit Trianon. As well as the 1901 experience he considers the visits made by Jourdain in 1902 and 1906, and by both in 1904, 1908 and 1910. With this background material providing useful context, he reprints their written accounts and discusses them in detail. Confusingly each wrote two accounts, the first in November 1901, longer ones at some point afterwards – Moberly and Jourdain claimed directly after the first, though there is controversy over this claim, exacerbated by them having destroyed the original documents, they said in 1906, after copying the texts into a notebook.

Certainly the first pair of accounts was sent to the Society for Psychical Research in October 1902, but the SPR did not find enough substance to them to warrant further investigation, which prompted the authors to conduct their own. Then before publication of the book in 1911 the publisher, Macmillan, asked the SPR to review it. The Society’s redoubtable Research Officer, Alice Johnson, met Moberly but the two did not hit it off. Johnson was naturally puzzled why, if the second set of accounts had been produced in December 1901 as Moberly claimed, only the first, shorter ones, had been sent to the SPR in 1902. The confusion over the dates and the failure to retain original documents did not instil confidence in their methods.

After looking at the vexed dating issue, Lamont compares the four accounts and finds evidence that rather than the later ones being merely an amplification of the earlier, as Moberly claimed in discussion with Johnson, the later ones were not written independently, indicate the subsequent inclusion of elements which evoke the eighteenth-century, and are more slanted to favour a paranormal interpretation. The conclusion has to be that Moberly was not entirely candid with Johnson.

The heart of Lamont’s evaluation is a breakdown of the adventure. He has visited Versailles and follows Moberly and Jourdain’s route section by section as best he can, given vagueness on their part and changes wrought by time, illustrating it with period illustrations and his own colour photographs. This is a forensic dissection of the ladies’ accounts and others’ observations on An Adventure, comparing them to the historical records for points of consistency or contradiction, and adding reports of strange experiences reported by later visitors; though as Lamont indicates, many of these may have been influenced by the percipient having read Moberly and Jourdain’s book. Complementing his research on site, Lamont has consulted a large number of archives, including the Bodleian Library in Oxford where Moberly deposited the papers accumulated by herself and Jourdain, allowing him to present a more rounded view than can be gleaned from their book alone.

Opening out the discussion, he draws parallels with other purported cases of retrocognition, seeing the past in the present, such as a ‘spectral house’ in Sir Ernest Bennett’s 1939 Apparitions and Haunted Houses, the 1957 Kersey case reported by Andrew MacKenzie in Adventures in Time, sounds heard aboard the RMS Queen Mary docked at Long Beach, California, and most significantly the 1951 Dieppe raid case (two English women on holiday in France have an experience which seems to link back to a previous event). Despite his book’s subtitle, Lamont stresses that Versailles falls into the category of retrocognition rather than physical time travel, though assigning a precise label is made more complicated by the interactions the ladies experienced: this was not a passive witnessing of supposedly past events unfolding before them.

Lamont mentions the occasional lazy dismissal of An Adventure as a hoax, and he shows that whatever the explanation, the ladies did not decide to cook up a plot to fool readers. To begin with they did not know each other well at that stage, rendering a conspiracy less likely, and if monetary gain, an uncertain prospect, had been the motive why wait a decade before publication? More plausibly, when Eleanor Sidgwick reviewed An Adventure in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, she attributed the experience to a combination of the heat, fatigue and a feeling of oppression leading to a sensation that the atmosphere was uncanny, added to which the delayed writing of the accounts allowed scope for the natural unreliability of memory. As a result, in her view the ‘supernormal claims’ were not sufficient to warrant examination. Moberly and Jourdain, undoubtedly feeling bruised by their contacts with the SPR, annotated their copy of the review ‘Not worth answering’, but Sidgwick may have been on to something.

Dame Joan Evans, who was bequeathed the rights to An Adventure, refused to allow any further editions after the fifth on the grounds that an explanation had been found to her satisfaction, in the form of a rehearsal for a tableau vivant by aesthete Robert de Montesquiou and a group of his friends. Lamont believes this theory does not hold up, though he suggests mysterious music heard by Jourdain in 1902 could be accounted for by military bands practising outside the grounds. In addition to assessing whether the pair, tired and in unfamiliar terrain, misinterpreted what they saw as an echo of past events when there was a natural cause, Lamont explores issues of fantasy-proneness, as suggested by experiences reported on other occasions by both ladies as paranormal, and the possibility they entered an altered state of consciousness as they walked in search of the small Trianon palace.

On the other hand he looks at debates about apparitions and the evidence for survival of bodily death to see if there is support in the literature for a paranormal component to what the ladies experienced in 1901, and surveys theories developed by psychical researchers which might account for what happened to them, including the SPR’s Guy Lambert’s theory that while they did not enter into an act of memory by Marie Antoinette, did in fact experience an act of telepathic communication with Antoine Richard, head gardener in the 1770s.

The Mysterious Paths of Versailles is well organised and excellently illustrated throughout, and is essential reading for anyone wishing to study the case in depth. One drawback is the lack of an index, which would have been valuable. Another is the price for the hard- and paperback versions, but the e-book has been pitched very reasonably. Whatever one thinks about the business, it is impossible to disagree with Lamont’s final words: ‘whatever did occur during Miss Moberly’s and Miss Jourdain’s visit to the Petit Trianon, the results have surpassed well beyond the expectations of an ordinary day of sightseeing on an August day in 1901.’